Imran Khan: How Pakistan’s enfant terrible went from playboy to political prisoner

The scenes that unfolded this past week in Pakistan’s capital city Islamabad were nothing short of extraordinary. As hundreds of paramilitary troops, dressed in riot gear, stormed the city’s high court, they roughly grabbed their former prime minister Imran Khan and bundled him into an armoured black van. From there, 70-year-old Khan was sent to the custody of the country’s anti-corruption authorities, sparking violent protests across the nation.

Khan’s political party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) called their leader’s arrest a political abduction, while some expressed shock at someone of Khan’s stature being treated like a “petty criminal”. PTI’s official handle declared an unofficial emergency for the citizens: “If you don’t come out to save your country today, then the scene we are seeing right now will continue till years to come,” the party tweeted. “Our dear Pakistan, it’s a never-before opportunity for you. Take it!”

Despite Internet outages, #ReleaseImranKhan and #BehindYouSkipper are trending online.

A LONG TIME COMING

Khan’s current predicament has been months in the making. Ever since he was ousted from the parliament in April 2022, Khan has had over 100 criminal cases piled up against him over allegations ranging from corruption to terrorism. Khan denies it all, alleging this is politically motivated by Pakistan’s military–which is the world’s sixth largest and wields an inordinate amount of power in the country–whom he accuses of plotting against him. Khan survived an assassination attempt in November last year, and dodged an arrest attempt later in March. Shortly before he was arrested, Khan posted a video accusing an intelligence official of trying to assassinate him.

Earlier in the week, while in prison, Khan was indicted in another case.

As the country sees a faceoff between Khan’s supporters and the military, many observers are forced to reflect on the legacy of Khan and wonder: How did a former cricketing hero and a sex symbol become one of the most controversial and influential political leaders of our time?

AT THE RIGHT PLACE AT THE RIGHT TIME

A survey by YouGov, a global public opinion and data company, puts Khan among the top 10 list of the most popular foreign politicians in the world. Raza Habib Raja, an academic and commentator on Pakistani affairs, told The Established that Khan’s entry into Pakistani politics came at the right time and the right place. “This was the 80s and 90s and Pakistan’s elite political class was getting increasingly unpopular, with accusations of corruption and political instability,” he says.

Bushra, a 53-year-old teacher from Islamabad and a staunch supporter of Khan, spoke to The Established on condition of anonymity due to security reasons given the present crackdown on Khan’s supporters. She said middle-class people like her rarely voted in Pakistan until Khan came along. “My ancestors were freedom fighters who migrated from India to Pakistan,” she says. “Despite that, we never voted because in the years to come, the political elite gained a reputation of being corrupt. We were completely disillusioned by politicians.” Khan isn’t perfect, Bushra added, but he’s the most sincere politician Pakistan has right now.

A GLORIOUS HEYDAY

Khan, Raja says, was an unconventional politician–savvy, well-groomed and with overseas education. He was already a larger-than-life personality who had built a legacy at a very young age. Khan was a cricketing star in a subcontinent that worships the game. He came from an upper-middle class family in Lahore, Pakistan’s second-biggest city, and had led the Pakistan team to a wild World Cup victory against England in 1992–a win that he described in his autobiography as “a battle to right colonial wrongs and assert our equality…on the cricket field.”

Former English cricketer and commentator Mark Nicholas called Khan a “cricketing god” and “exceptional leader of men” in a 2020 column. “Of the myriad gifts, his greatest may be the way he holds it together under pressure,” Nicholas wrote. “This is achieved through both resilience and self-belief; single-mindedness and desire.”

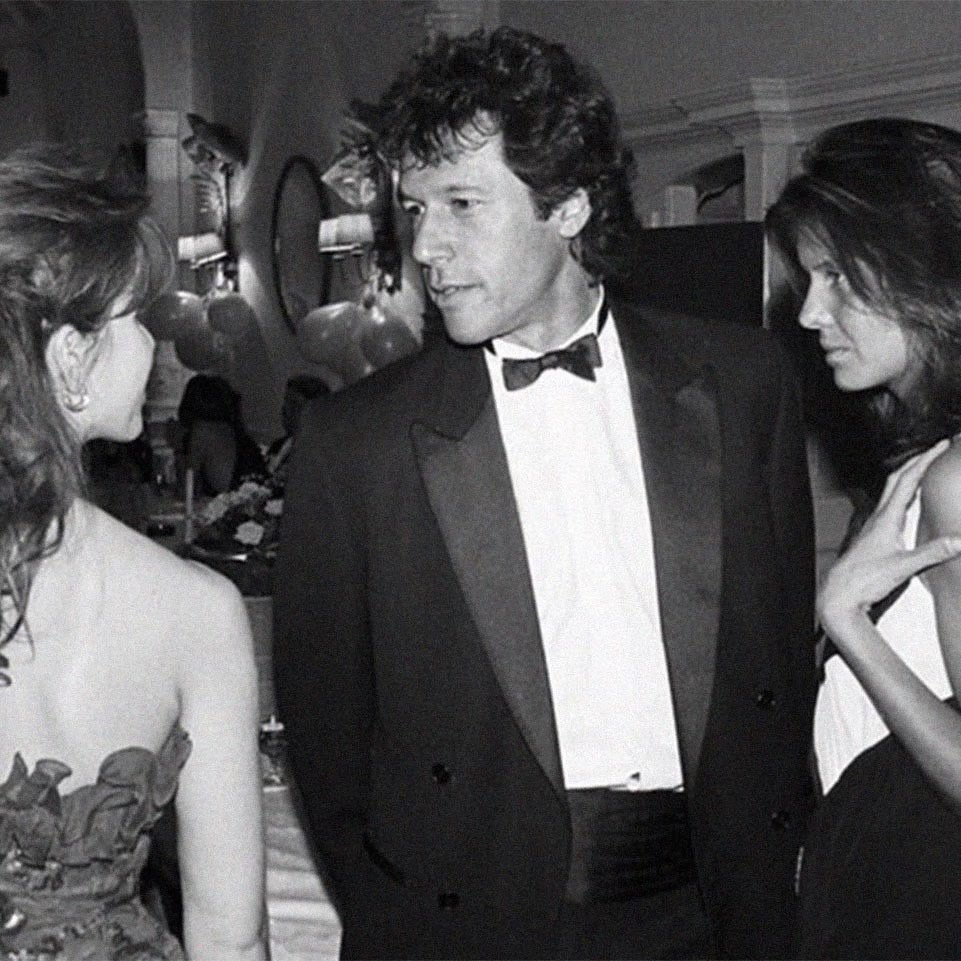

Off the cricket field, Khan espoused the affluent, rock-and-roll generation of Pakistan who partied with the British aristocracy. His past interviews reveal many a night spent at London’s most exclusive nightclubs such as Annabel’s and Tramp. His outings were a tabloid fixture, wherein he was seen with women such as Sita White (with whom he had a child that he doesn’t acknowledge publicly), former TV personality Susannah Constantine (who, in her memoir, wrote that Khan allegedly told her, “You have perfect breasts”) and artist Liza Campbell among others. “I have never claimed to be an angel,” Khan told The Guardian in a 2006 interview. “I’m a humble sinner.”

Khan’s sex appeal is undeniable. Author Aatish Taseer describes him as “one of those rare figures, like Muhammad Ali, who emerge once a generation on the frontier of sport, sex, and politics.”

Uzair Younus, the Vice President - South Asia at The Asia Group, a global advisory firm, told The Established that Khan has been controversial from the start. On the field, however, Khan won the adoration of generations for more than his cricket skills. “He was very aggressive in terms of the strategies he deployed as a captain,” says Younus. “He also pushed for a change in the status quo in the cricketing ecosystem, particularly the insertion of neutral umpires.”

These traits, Younus adds, continue to reflect in his politics. “He remains a key disruptive force, trying to bend and change the rules of the game,” he says. “He keeps his political opponents off balance.”

MALIGNED AND MISREPRESENTED?

Khan’s voracious social life put his relationships under tough scrutiny. His marriage to British writer and filmmaker Jemima Goldsmith was controversial for the nine years it lasted. Goldsmith was 21 when she married Khan, who was 42, and she embraced Islam and moved to Pakistan just when her husband was getting into politics. In 2004, the couple divorced, saying Khan’s political life “made it difficult for her to adapt to life in Pakistan.”

Khan was briefly married to Reham Khan, a BBC presenter, which dissolved in 10 months. In 2018, the year he became the prime minister, Khan married his spiritual advisor, Bushra Maneka, with whom Khan says he shares only a “spiritual” relationship. “Every time I have interacted with her, she has been in purdah,” Khan said in an interview. “My interest in her lies in the fact that I have not seen or met anyone with her level of spirituality.”

The transition from a sex symbol to a pious “born again” Muslim has been key to Khan’s political rise. He evokes Islamic values in his political speeches and is anti-West in his stance. Khan also actively distanced himself from what he calls the Western media’s “obsession” with his youthful exploits, which he says reeks of Western stereotypes and bias. Not many outside Pakistan know that Khan is also one of the biggest philanthropists in the country who opened a world-class cancer hospital inspired by his mother’s battle with cancer.

Bushra, Khan’s supporter, said that many like her choose not to delve into his past. “Everyone makes mistakes,” she says. “He’s a human, not a prophet. We look at what he’s doing for the country, not dig into his personal life.”

ANOTHER NAIL IN THE COFFIN

Much of his image-building is also credited to the Pakistani military, of which he’s ironically the loudest critic right now. Azeem Ibrahim, a former advisor to Khan, wrote in a Foreign Policy column in 2022 that Khan played “the game” in Pakistani politics to get into office in 2018 by being “the army’s man”. The Pakistani military denies it but the institution that’s ruled the country for nearly half of its 75 years of existence, is known to make or break its political leaders. But experts had warned that Khan’s personality and policy positions wouldn’t keep that up for too long.

Today, Khan challenging the status quo of the military has shaken the military itself.

Raja, meanwhile, calls Khan the classic case of Frankenstein’s monster. “The military spent years promoting him and building this messiah sort of image of him for the people,” he says. “Now that’s proven costly for them.”

As Khan looks at custody for at least another week, his supporters are seen clashing with the military and, as seen in some videos, ransacking army personnel’s homes. Some analysts say the military might be planning to not just take Khan’s leadership out of the picture, but ban his party entirely.

Bushra says there’s a lot of anger on the ground and supporters are willing to protest for as long as possible to get Khan out of prison. In line with Khan’s accusations, she, too, believes his life is in danger. “His life depends on the response of his people,” she says. “And so, we will not let this go.”

Younus says that the implications of Khan’s arrest goes beyond Pakistan. “We can say with certainty that there will be more crises and instability and Pakistan will become more and more insular in its approach,” he says. “If this [crisis] continues and no resolution is reached, the shockwaves that’s currently jolting Pakistan will be felt around the world.”

Published by: The Established

Reporter: Pallavi Pundir