Mother my Tongue

Growing up away from home means a fractured relationship with the language of one’s own. How does one reclaim it?

One muggy evening, during one of my meticulously scheduled calls with my mother, she startled me with a quick prelude in chaste Garhwali. I stopped short when she said, “It’s time for you to learn Garhwali.” This was a calling, and it reminded me of how Frodo Baggins, urged by the Ring handed down by his uncle, saved the Middle Earth; and Luke Skywalker, with his twin sister Leia, led the rebels to victory and, in the process, found his real father. Here, though, my mother’s words rang through the static connection inside the Delhi metro, and evoked a reluctant hero. This was a quest I wasn’t quite willing to embark upon. “Yes, sure, later, not now,” I mumbled.

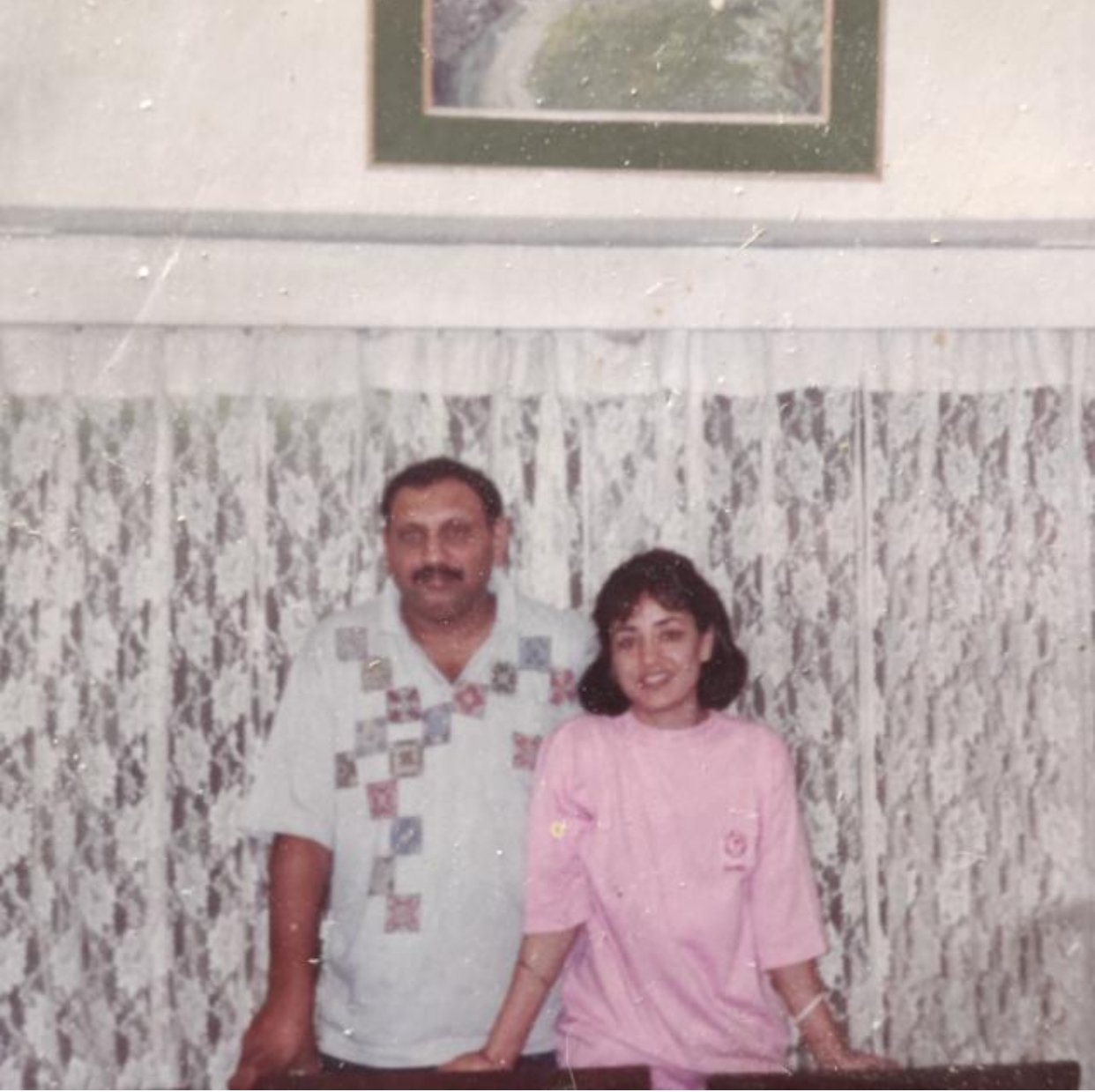

The lessons, I suppose, must start at home, except that home had never been one place for long. Growing up in as disconnected a world as the Indian army, posted in the remotest corners of the Northeast, alienated me from my mother’s Garhwali roots. Unlike many around me, apart from the habitual Hindi at home and polite English at mess dinners and social gatherings, I did not have the advantage of having a mother tongue others didn’t understand. And growing up in itself is tough, eh? You learn and unlearn in a matter of hours, get busy adjusting to a new cantonment every two-three years; between making new friends and losing old ones, you’ve suddenly entered adulthood. When I moved out of home to Delhi, to study and then work, I was everything but a Garhwali.

The only exposure to Garhwali was when I visited my maternal grandparents. As a child, my only contribution to educating myself was to learn apt cuss words in the language, which I would then aim at my brother. My aunts, grandmother and my mother gleefully gossiped away many a post-meal siestas in Garhwali. So, the language was always familiar, but distant. It was a language that did not come from my home; that absence of belongingness, perhaps, just grew more tangible in the years to come.

Things began to change as I grew older. At home, for instance, I observed my mother’s brusque Garhwali to perk up a mundane conversation. “Kujan kujan,” she once ended a discussion with (“Maybe, maybe”, but is effectually a Garhwali version of “Whatever” and a defiant equivalent of a mic drop). My non-Garhwali father sniggers, and we laugh along. “It sounds funny,” my father said, to which she replied, “Well, it doesn’t hold the same emotion in any other language.”

This initial inquiry into my roots spiralled into an awakening of sorts. Food, the most common denominator for cultural identities, and an Achilles heel which brings me home once every few months, was one of the departure points. As the warm, afternoon winter sun pours into our verandah, the house immerses itself in the fragrance of tadka in tor kulat, a thick, hardy lentil preparation, along with steamed rice, kitchen garden spinach, and mandve ki roti. Phaanu dal is another favourite, which is a mix of lentils and gahat, lending it a rich, creamy texture. This quintessential “pahadi” food, my mother tells me, not only beats the mountain chill, but is also good for cholesterol (a constant struggle in my family). At night, we promptly pop in a chunk of jaggery after dinner, an antidote for indigestion as well as cold. Ghee is not an enemy either. “It is good for bones,” my mother tells me, gleefully scooping a homemade dollop and dropping it on our plates. The particularly brittle January cold is tackled with just the right amount of brandy and roasted peanuts.

Back in Delhi’s urban landscape, however, that alienation continues. For one, it’s hard enough to find another Garhwali in this vast metropolis to share this piece of identity with. It’s a speck, really, this piece of identity — an absurd claim to a language and culture that comes from, first, ignorance, and then, some last-minute curiosity. If I do chance upon someone from my side of the town, we end up scrunching our noses at our generation’s apathy, and then sombrely realise that we are the ones who are lost.

So, what are Garhwalis really like? Of course, we all have our personality mutations, but some traits remain constant. Garhwalis, I learnt, are people without filters. If you want an honest opinion, scathing as it may be, look no further. As your Garhwali friend gleefully churns out every aspect of your shortcoming, observe a glint of satisfaction on their face; it’s not joy at your discomfort, just the happiness that you went to them first. And can you imagine a sentence without sarcasm? Well, Garhwalis can’t. Which is probably why we don’t take ourselves seriously. We know the lore of the laidback hill folks, and own it with all seriousness.

Somehow, in all this, I found a common ground to embrace the identity with all its idiosyncrasies. Perhaps, staying away from family for more than a decade has toned down my quirks, which is why celebrating what I know becomes crucial. One day, I came across UNESCO’s list on the disappearing languages of the world, which put Garhwali in the “vulnerable” category. Garhwali, it said, is “unsafe”. Alarmed, I rang my mother up and said, “I want to learn Garhwali”. After what seemed like a concussion caused by shock and absolute joy, she scheduled a series of phone classes. Let’s start with the basics, she said. My fervour fizzled out sooner than expected.

But I still hold on to the dream of reclaiming that speck of an identity, the one that I lost out on, and the one I feverishly want to make my own. When my friends tease me as a “north Indian”, I correct them with the intensity of a zealot. “Who are Garhwalis, anyway?” they ask. I spell out geographical boundaries. “Can you speak the language?” I shake my head, but assure them that I’m just getting started. It’s time to call my mother.

Published by: The Indian Express

Reporter: Pallavi Pundir